21 July 2023 | In September 2022, the Swiss Entrepreneurship Program (Swiss EP) organized an immersion week in Switzerland visiting 03 innovation parks, 01 incubation program, 01 scale-up program, 01 SME program, and 01 corporate innovation center. The week also includes meetings at SECO Headquarters and Crypto Valley as well as discussions with the founders of CV VC, World Innovation Forums, and Blue Callom.

The immersion week was followed by the Peer Exchange Meetup 2022. Representatives of partner organizations from Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, Macedonia, Peru, Serbia, and Viet Nam were gathered in Zurich to share experiences and best practices from their countries as well as find similarities and inspiration. Experienced ecosystem builders – mainly from Switzerland, but also including Germany, Norway, and the US – provided inputs on trends in startup programs, financial sustainability, community building, international partnerships, academia-driven entrepreneurship, sector-vertical deep dives, ecosystem scaling, and funding opportunities.

The first highlight of the two weeks in Switzerland is the openness and friendliness of the Swiss hosts and experts. Swiss EP’s global management in Zurich made the first introductions. Then the immersion team from Viet Nam proactively scheduled pre-visit calls and in-person meetings in Zurich, Biel, Zug, Bern, and Lausanne. The entrepreneurial culture worked very well as Swiss entrepreneurs, incubator managers, university researchers, and government officials kept connecting the immersion team to their friends and partners. Meetings were conducted in offices, cafes, restaurants, and even dinners at home. Every question raised by the immersion team was well responded to. Sometimes the responses were in line with experience in Vietnam. When the responses were surprising the exchanges were so mutually exciting. Last but not least, by doing all the things themselves – from designing the agenda, getting people and meetings scheduled, traveling with various transportation means, and so much interacting with people in Switzerland – the immersion team gained a really precious experience of somehow understanding the way Swiss people think and how the system works.

The following are key findings from discussions and observations, together with thoughts on what lessons are for Viet Nam. In addition to experience and lessons learned, the immersion trip did provide a lot of food for thought.

The Roles of Governments

For years, Switzerland maintains the top position of an innovation leader in various international rankings such as IMD World Competitiveness (#1 in 2021), Union Innovation Scoreboard (#1 in 2020), Global Innovation Index (#1 in 2021), and Bloomberg Innovation Index (#3 in 2021). The federal government of Switzerland, however, gave R&D spending a low budget in comparison to other European countries and hardly supported private R&D (Busch, 2022).[1] Meanwhile, the federal government imposes seven strict principles as follows.

- (Almost) no top-down innovation or cluster policy (bottom-up focus)

- Science focus:

- No direct financing to firms

- Matching funds (firms/cantons)

- Technology-neutrality / No industrial policy

- Large degree of Autonomy of actors

- E.g. International cooperation; technology transfer

- Generous general funding

- Internal competition in order to be internationally competitive

- Simple laws (clear separation of competencies, few articles) and instruments

From Switzerland’s perspective, this approach is bottom-up where the federal government provides very little resources. The federal government spent CHF 4 million on six locations of Switzerland Innovation Parks (Bush, 2022) while just the Biel location got CHF 20 million from the canton government for their building (Gfeller, 2022).[2]

From Vietnam’s perspective, both top-down and bottom-up approaches are deployed to promote innovation in Switzerland. The federal (central) government allows the canton (municipal) governments to be autonomous (in terms of what to do and which industries to focus on) and generously fund efforts to make innovation happen, for instance.

The federal government of Switzerland is very much active in terms of promoting the creation of startups, including direct support to the startups. There were surprisingly not many startups come from universities. This has been changing with the government’s large support for basic research. While it is hard to get evidence, there should be good linkages between the universities and the industries because the funding mechanism is matching. Research only gets government funds when there is funding from industries.

Still, IPs are always challenging in both countries, Switzerland and Viet Nam.

Understanding of Innovation

While entrepreneurship and innovation are interchangeable in Viet Nam, there seems to be a separation between the two concepts in Switzerland.

Granstrand & Holgersson (2020)[3] define an innovation ecosystem as an evolving set of actors, activities, and artifacts, and the institutions and relations, including complementary and substitute relations, that are important for the innovative performance of an actor or a population of actors. Whereas “innovation is the process that turns ideas into business success,” said Roland Keller (Head of Innovation Culture, Swiss Post).

Thomas Gfeller (SIP BB) sees innovations as outputs of the innovation parks. They are IPs, prototypes, tested products, and research results. In addition, Roland Keller (Swiss Post) considers innovation as the process that turns ideas into business success.

Entrepreneurship is perceived as the entrepreneurial spirit attached to people – the entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs desire to change things by creating new value and then capturing wealth. As startups are drivers of innovation, entrepreneurs need to be well-equipped with business skills.

Yes, it takes two (entrepreneurship and innovation) to tango. In a normal situation, businesses focus on optimizing their resources for economic gains thus perceptions about the values of commercializing new products, new services, or introducing new ways of doing business are usually vague. But in difficult times and harsh competition, the difference between death and alive may be innovations (Dang, Napier, and Vuong, 2012).[4]

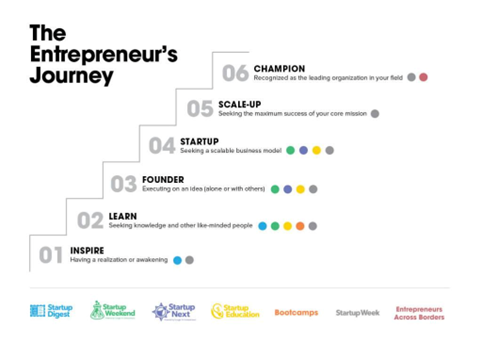

A separation between entrepreneurship and innovation helps entrepreneurship support organizations (ESOs) be clear on what they should do to support entrepreneurs and promote innovations. The entrepreneur’s journey is an anatomy of the innovation process. While an entrepreneurship ecosystem focuses on the entrepreneurs (the people), an innovation ecosystem focuses on innovative outputs (products, services, and processes). In other words, entrepreneurship is about mindset and innovation is about toolset.

Innovation Park: Operation and Business Model

There are six locations of Switzerland Innovation Park (or Switzerland Innovation Foundation). Each park is a member of the foundation. The parks are independent. Each focuses on specific industries based on the competitive advantages of the locations and market demand. The latter is often defined by the needs of local corporations and SMEs. For instance, SIPs in Biel and Zurich focus on smart-factory and aerospace respectively.

Among the six locations, SIP Beil/Bienne is the most advanced. Founded in 2012, the most application-focused SIP BB reached break-even in 2022. With the industries in their DNA, SIP BB keeps responding to the key question “What do industrial companies need?” In the beginning, the founder and president of SIP BB Thomas Gfeller spent six months interviewing industry executives. The needs are as follows.

- People who know how to use, scope, and partner with others to do innovation.

- Proposition: Fast and cost-effective access to people (talents)

- Technology platform to test and prototype

- Proposition: Fast and cost-effective access to people (talents), equipment, and machine

- Place for talents and technology to meet for implementing the innovations and applications

- Proposition: Services to the industries such as testing, prototyping, and application researching.

Physical space and location are critical to the success of an innovation park. The space attracts people, especially talented engineers and researchers who need the equipment and machine to play with their innovative ideas. The space also generates revenues – i.e., rented offices and events. Although space revenue can reach a limit shortly and hardly help the innovation park reach break-even, this source of revenue generates healthy cash inflows in the early days. Transportation to the innovation parks is very convenient. In Biel and Zurich, it takes less than 3 minutes to walk to the parks from the train and bus stations. In Lausanne, EPFL Innovation Park is actually a couple of buildings within the University’s campus.

It is worthnothy that the business of innovation parks cannot base on metters square. Thomas Gfeller emphasizes that the outputs and products of an innovation park are innovation units. In other words, an innovation park is manufacturing innovations. In the case of SIP BB, their business model is crystal clear: offering services for testing, researching, and prototyping. SIP BB just takes service fees. Any intellectual properties belong to customers who are industries and universities.

The operation and business of the three visited innovation parks in Biel, Zurich, and Lausanne reveal the triple helix model of innovation where academia (universities), industries, and government interact.

Rethinking the role of government

As both ecosystems of entrepreneurship and innovation require long-term vision, the government should have a larger role with their constant support. The government, especially the local government, is not only an initiator and ignitor but also a key stakeholder. Despite its privately-run operation, SIP BB reserves 5% of the equity stake for local government.

When SIP BB was established in 2012, the total capital of the innovation park was just CHF 150,000. Of which, private investors contributed 8%. The other shareholders were the canton government, the Biel city government, and the University of Applied Science. Since Innovation Park was not able to reach break-even in the early years, private investors kept injecting money and gradually increased their stakes. When the canton government provided SIP BB with a piece of land and a grant of CHF 20 million to build up their first building, SIP BB raised CHF 40 million for construction, equipment, and machine from private investors. As of September 2022, 95% of SIP BB’s equity was privately held.

The public-private partnership is necessary. While private investors contribute cash and business connections, local governments’ support includes space (land), infrastructure (especially public transportation connect to the innovation park), and a master plan for allocating universities, business premises, and residential areas close to the parks. Last but least, local governments are able to promote the innovation parks with special supporting policies (sometimes mentioned in Viet Nam as sandbox policies).

For example, in Zug where the Crypto Valley locates, the canton government allows blockchain companies to pay tax in cryptocurrencies. Such an encouraging policy! As in many cities and countries, cryptocurrencies are not legally considered. “What risk does the Zug government face with this policy?” Honestly addressed the questions, the representative of Zug who is in charge of supporting the blockchain businesses and community unveiled that no company has paid tax in cryptocurrencies so far. “They were afraid of the rising valuation of cryptocurrencies,” he smiled.

In Viet Nam, Buon Ma Thuot – the capital city of the central highland region – waives personal income tax for experts and innovators in the first 5 years they are working in the city as an effort to promote innovation and entrepreneurship. Similar policies will be applied in Ho Chi Minh City.

Corporate engagement

Innovation parks should consider themselves independent, viable businesses and pursue financial sustainability. To this end, the leadership and management of innovations park should have ownership of the parks. This is clear in SIP BB where the innovation park is structured as a company with a board of directors and all executives are shareholders. In Zurich and Lausanne, where the public shareholders are still a majority, both directors apparently show their ownership, in terms of defining what needs to be done and where and how to find necessary resources to get things done.

Cyril Kubr has both business and academic experience before leading Switzerland Innovation Park Zurich. He is responsible for the development and implementation of the ETH Zurich strategy at the park. Already got funding from the Canton of Zurich and ETH Zurich, Cyril sets his own objective to drive SIP Zurich to be financially sustainable with private partnership and investment. In the case of Jean-Philippe Lallement, who has been in the business for 30 years, the leadership’s autonomy of the Innovation Park from EPFL is a key to success despite a tight relationship. Indeed, the Vice President of EPFL is the President of the Innovation Park. The Managing Director is on his own when making investment and operation decisions. For example, every building of EPFL Innovation Park has a different financing structure and EPFL pays CHF 7 million in rental fees to the Innovation Park annually.

Corporate engagement is emphasized at all innovation parks. In Biel, the establishment of SIP BB is a result of an interview series with corporate executives and SME owners on what they need. It is no surprise when those executives and business owners become clients of Innovation Park. As many are testing and prototyping their innovative ideas, visitors are encouraged not to take photographs in SIP BB. In Zurich, Cyril was arranging a deal with a large real estate company to transform the hangars and airfield into coworking spaces, maker spaces, and offices. In Lausanne, EPFL Innovation Park, in collaboration with corporate partners, is developing an „innovation district.“

As most, if not all, Swiss EP’s partner organizations, as well as the other entrepreneurship support organizations (ESOs) in Viet Nam, are eyeing corporations as a sustainable and prosperous source of revenues, how Switzerland’s innovation ecosystem gets corporations engaged is of strong interest. There is no secret sauce. Getting corporations engaged with the ecosystem is challenging everywhere. So, if working hard still does not make it then working harder is needed. In addition to telling the corporate executives how wonderful the startups are and what their excellent products and services can do for them, the ESOs can try a reverse approach. Spending time empathizing with the corporations, then constructing the corporate problems and organizing entrepreneurship programs for startup founders and innovators to sprint their solutions.

Mike Baur, the cofounder and CEO of Swiss Ventures Group, has been trying so much to reach the corporations that he shares a formula at the PEM 2022. “Make a list of 10 new corporations on Monday. Call them on Tuesday to schedule meetings. And never schedule the meetings on Friday which is basically the corporate weekend!”

University as the source of talent and knowledge

It is apparent that innovation parks must be located nearby universities as a constant source of talent and novel knowledge. In all three visited innovation parks, there are university shareholders, indeed.

For instance, Bern University of Applied Sciences is a founding shareholder of SIP BB. The Biel Campus of BFH is in front of SIP BB, just across the street. Switzerland Innovation Park Zurich is actually managed by ETH Zurich (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zürich). EPFL Innovation Park in Lausanne is within the campus of EPFL – as part of the university.

While there is a lot of innovation and entrepreneurship center in universities in Viet Nam, it is necessary to highlight the quality of human resource. (This is, by no means, to say that human resources in Viet Nam is no good.) It is noticed that Swiss universities are world class.

- In the 2022 edition of QS World University Rankings, ETH Zurich was ranked 8th in the world, placing it as the fourth-best European university after the University of Oxford, the University of Cambridge and Imperial College London.

- The QS World University Rankings ranks EPFL 14th in the world across all fields in their 2020/2021 ranking, whilst Times Higher Education World University Rankings ranks EPFL as the world’s 19th best school for Engineering and Technology in 2020.

[1] Christian Busch, 2022. The Swiss Government’s Approach to Promote Innovation, Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation.

[2] Thomas Gfeller, 2022. Switzerland Innovation Park Biel / Bienne: Meeting with BK Holdings.

[3] Ove Granstrand and Marcus Holgersson (2020). Innovation ecosystem: A conceptual review and a new definition. Technovation, 90-91.

[4] Dang Le Nguyen Vu, Nancy K. Napier, and Vuong Quan Hoang, 2012. It Takes Two to Tango: Entrepreneurship and Creativity in Troubled Times – Viet Nam 2012. CEB Working Paper No. 12/022

[…] sáng tạo, các quốc gia phát triển như tại Hoa Kỳ, Nhật Bản (Dũng, 2018)[vi], Thụy Sĩ (Dũng & Dũng, 2023)[vii], Singapore.. cùng áp dụng mô hình triple helix gắn kết […]

LikeLike

Hệ sinh thái đổi mới sáng tạo Thụy Sĩ – Những điều Việt Nam cần làm

Tháng chín năm ngoái, một nhóm các nhà đổi mới sáng tạo của Việt Nam đã trải qua hai tuần học hỏi tại Thụy Sĩ thông qua chương trình trao đổi doanh nhân toàn cầu của Swiss EP. Tuy ngắn ngủi nhưng các cuộc thảo luận, quan sát và gặp gỡ đã để lại ấn tượng sâu sắc đến mức các thành viên tham gia quyết định viết một blog chia sẻ về những điều cần nghiêm túc cân nhắc cho Việt Nam.

Vai trò chủ động của chính quyền địa phương

Trong nhiều năm, Thụy Sĩ duy trì vị trí dẫn đầu trong các bảng xếp hạng quốc tế về đổi mới sáng tạo. Tuy nhiên, chi tiêu ngân sách R&D của Chính phủ Liên bang rất thấp so với các nước châu Âu khác và hầu như không bỏ tiền cho R&D của khu vực tư nhân.

Để làm điều này, Chính phủ Liên bang Thụy Sĩ áp dụng bảy nguyên tắc nghiêm ngặt: không đưa ra chính sách đổi mới sáng tạo áp đặt từ trên xuống hoặc chính sách phát triển cụm ngành ưu tiên mà đi theo nhu cầu từ thị trường (bottom-up); trọng tâm ngành khoa học là không tài trợ trực tiếp cho các công ty mà sử dụng hình thức đối ứng (matching fund) giữa các công ty với chính quyền địa phương; duy trì tính trung lập về công nghệ, hay nói cách khác không có chính sách ưu đãi riêng cho các ngành công nghiệp; cho phép mức độ tự chủ lớn của các tác nhân trong hệ sinh thái đổi mới sáng tạo; đưa ra những khoản tài trợ chung hết sức hào phóng; kích thích cạnh tranh nội bộ để đạt được năng lực cạnh tranh quốc tế; và thủ tục pháp lý cùng các công cụ điều chỉnh đơn giản.

Từ góc nhìn của Thụy Sĩ, đây là cách tiếp cận từ dưới lên, nơi Chính phủ Liên bang cung cấp rất ít nguồn lực và các tác nhân ở địa phương sẽ là nhà đầu tư chủ yếu. Ví dụ, Chính phủ Liên bang đã chi 4 triệu CHF cho sáu công viên đổi mới sáng tạo của Thụy Sĩ, trong khi chỉ riêng công viên ở Biel đã nhận được 20 triệu CHF từ chính quyền bang để xây tòa nhà của mình.

Từ góc nhìn của Việt Nam, Thụy Sĩ đang sử dụng cả hai cách tiếp cận từ trên xuống và từ dưới lên để thúc đẩy đổi mới sáng tạo. Ví dụ, Chính phủ Liên bang (trung ương) cho phép chính quyền bang (địa phương) tự chủ về những việc cần làm và những ngành công nghiệp cần tập trung, trong khi vẫn đưa ra các khoản tài trợ chung hào phóng cho những nỗ lực thực hiện đổi mới sáng tạo ở địa phương.

Thụy Sĩ rất tích cực trong việc thúc đẩy tạo ra các công ty khởi nghiệp (startup), một trong những động lực chính của quá trình đổi mới sáng tạo. Chính quyền cung cấp các hỗ trợ trực tiếp và gián tiếp cho startup. Điều đáng ngạc nhiên là không có nhiều startup đến từ trường đại học, tuy nhiên điều này đang thay đổi nhờ các khoản tài trợ lớn của khu vực công cho các nghiên cứu cơ bản. Mặc dù khó có được bằng chứng cụ thể nhưng người ta tin rằng có một mối liên hệ khá tốt giữa các trường đại học và ngành công nghiệp nhờ cơ chế tài trợ đối ứng. Một nghiên cứu chỉ nhận được tiền của Chính phủ khi nó gọi được tài trợ đối ứng từ các doanh nghiệp.

Vì đổi mới sáng tạo đòi hỏi tầm nhìn dài hạn nên các chính phủ cần có vai trò lớn hơn trong việc hỗ trợ liên tục này. Chính phủ, đặc biệt là chính quyền địa phương, không chỉ là người khởi xướng mà còn nên là một bên liên quan chính. Ví dụ, công viên đổi mới sáng tạo SIPBB vẫn có 5% cổ phần do chính quyền địa phương nắm giữ.

Khi mới thành lập năm 2012, SIPBB chỉ có 150.000 CHF, trong đó nhà đầu tư cá nhân đóng góp 8%. Các cổ đông còn lại là Chính quyền bang Bern, Chính quyền thành phố Biel và Đại học Khoa học Ứng dụng Bern. Vì công viên đổi mới sáng tạo không thể hòa vốn trong những năm đầu, các nhà đầu tư tư nhân tiếp tục bơm tiền và tăng dần tỷ lệ nắm giữ cổ phần của họ. Khi chính quyền bang cấp cho SIPBB một mảnh đất và khoản trợ cấp 20 triệu CHF để xây dựng tòa nhà đầu tiên, SIPBB đã huy động được thêm 40 triệu CHF từ các nhà đầu tư khác cho việc xây dựng, mua sắm thiết bị và máy móc. Tại thời điểm tháng 9/2022, tư nhân đã nắm giữ 95% cổ phần của công viên đổi mới sáng tạo này.

Có thể nói, sự tham gia trực tiếp của khu vực công trong những ngày đầu là nhân tố kích thích và tạo lòng tin cho khu vực tư nhân tiếp tục dấn tới. Trong khi các nhà đầu tư tư nhân góp tiền của và các mối quan hệ kinh doanh thì sự hỗ trợ của chính quyền địa phương – bao gồm không gian (đất đai), cơ sở hạ tầng (đặc biệt là giao thông công cộng kết nối với công viên đổi mới sáng tạo) và kế hoạch tổng thể để phân bổ các trường đại học, cơ sở kinh doanh và khu dân cư gần công viên – rất có ý nghĩa.

Hơn thế nữa, chính quyền địa phương có thể thúc đẩy các công viên đổi mới sáng tạo bằng các chính sách hỗ trợ đặc biệt (mà ở Việt Nam hay gọi là các sandbox chính sách). Ví dụ, ở Zug, nơi tọa lạc của Thung lũng Crypto, chính quyền bang cho phép các công ty tiền điện tử và blockchain có thể truy cập các dịch vụ ngân hàng truyền thống để thực hiện các hoạt động; sử dụng tiền điện tử để thanh toán dịch vụ công và trả thuế. Thật là một chính sách đáng khích lệ! Ở nhiều thành phố và quốc gia khác, tiền điện tử vẫn chưa được coi là đồng tiền hợp pháp.

Vậy chính quyền Zug phải đối mặt với những rủi ro gì khi ban hành chính sách này? Thành thật mà nói, đại diện của Zug, người chịu trách nhiệm hỗ trợ các doanh nghiệp blockchain và cộng đồng, tiết lộ rằng cho đến nay không có công ty nào trả thuế bằng tiền điện tử cả mà vẫn trả bằng tiền CHF vì “họ sợ sự gia tăng giá trị của tiền điện tử”, ông cười nói. Như vậy, trên thực tế, rủi ro của chính quyền khi bật đèn xanh cho các thử nghiệm đổi mới sáng tạo có thể thấp hơn so với những lo ngại ban đầu.

Việt Nam hoạt động trong một môi trường tập trung chặt chẽ và ít có sự linh hoạt ở các địa phương hơn. Các nguồn lực và chính sách về khoa học, công nghệ và đổi mới sáng tạo vẫn chủ yếu được phân bổ theo dạng từ trên xuống. Chính quyền địa phương chưa có nhiều kinh nghiệm để đầu tư sâu cho hệ sinh thái đổi mới sáng tạo. Tuy nhiên, có tín hiệu cho thấy tình trạng này đã bắt đầu thay đổi ở một số tỉnh thành.

Buôn Ma Thuột – thủ phủ của khu vực Tây Nguyên – đã đưa ra một quyết định quan trọng khi chấp nhận miễn thuế thu nhập cá nhân cho các chuyên gia và nhà đổi mới sáng tạo đến làm việc tại thành phố trong 5 năm đầu tiên. Đây là một trong những nỗ lực nhằm thúc đẩy đổi mới sáng tạo và khởi nghiệp ở khu vực. Chính sách tương tự cũng đã được áp dụng tại TP. Hồ Chí Minh từ ngày 1/8 năm nay.

Trong năm năm qua, TP.HCM cũng là địa phương đầu tiên (và duy nhất) đang áp dụng cơ chế tài trợ đối ứng để chính quyền có thể đầu tư trực tiếp cho các startup nhằm thúc đẩy việc tạo ra các công ty khởi nghiệp mới.

Công viên đổi mới sáng tạo – “Trái tim” của hệ sinh thái

Thụy Sĩ có sáu công viên đổi mới sáng tạo nằm rải rác trên khắp đất nước. Mỗi công viên đều độc lập, tập trung vào những ngành công nghiệp cụ thể dựa trên lợi thế cạnh tranh của địa điểm đặt công viên và nhu cầu thị trường. Nhu cầu thị trường được xác định bởi nhu cầu của các tập đoàn và doanh nghiệp vừa và nhỏ tại địa phương. Ví dụ, công viên đổi mới sáng tạo ở Biel tập trung vào nhà máy thông minh trong khi công viên đổi mới sáng tạo tại Zurich chú trọng vào hàng không vũ trụ.

Trong số sáu công viên, SIPBB ở Biel là vượt trội hơn cả khi đã đạt điểm hòa vốn vào năm 2022, sau hơn một thập kỷ hoạt động. SIPBB liên tục trả lời câu hỏi “Các công ty công nghiệp cần gì?”. Ban đầu, người sáng lập Thomas Gfeller dành sáu tháng để phỏng vấn các giám đốc điều hành trong nhiều ngành công nghiệp, từ đó xác định được các nhu cầu của ngành là: (1) cần những con người biết cách làm việc, mở rộng phạm vi và hợp tác với người khác để đổi mới sáng tạo, (2) cần những nền tảng công nghệ để thử nghiệm và chế tạo sản phẩm mẫu, và (3) cần một nơi để các tài năng công nghệ gặp gỡ, tụ hợp và thực hiện các hoạt động đổi mới sáng tạo.

Dựa trên ba nhu cầu đó, SIPBB đã đưa ra đề xuất cho các doanh nghiệp, bao gồm các gói dịch vụ cho phép truy cập nhanh và tiết kiệm tới các chuyên gia, thiết bị, máy móc và các dịch vụ cho ngành công nghiệp như thử nghiệm, tạo mẫu, nghiên cứu ứng dụng.

Không gian vật lý và vị trí đóng vai trò hết sức quan trọng đối với sự thành công của một công viên đổi mới sáng tạo. Mặc dù doanh thu từ hoạt động cho thuê văn phòng và tổ chức sự kiện có thể đạt đến giới hạn trong thời gian ngắn và hầu như không giúp công viên hòa vốn nhưng nguồn doanh thu này tạo ra dòng tiền lành mạnh trong giai đoạn khó khăn ban đầu. Giao thông đến các công viên đổi mới sáng tạo luôn phải thuận tiện. Ở Biel và Zurich, chỉ mất 3 phút đi bộ từ các bến tàu, nhà ga và xe buýt đến tòa nhà công viên. Ở Lausanne, công viên đổi mới sáng tạo nằm ngay trong khuôn viên của Viện Kỹ thuật Liên bang Lausanne (EPFL)

Cần chú ý là việc kinh doanh các công viên đổi mới sáng tạo không thể tính theo diện tích mặt sàn. Thomas Gfeller nhấn mạnh rằng đầu ra và sản phẩm của một công viên đổi mới sáng tạo là các đơn vị (unit) đổi mới sáng tạo. Nói cách khác, một công viên đổi mới sáng tạo là một nơi sản xuất những “sản phẩm” đó. Trong trường hợp của SIPBB, mô hình kinh doanh của họ rất rõ ràng: cung cấp dịch vụ thử nghiệm, nghiên cứu và tạo mẫu. SIPBB chỉ nhận phí dịch vụ. Bất kỳ tài sản trí tuệ nào cũng thuộc về khách hàng là các hãng công nghiệp và trường đại học.

Tại Việt Nam, những nỗ lực đầu tiên trong việc phát triển các công viên khoa học công nghệ đang dần được triển khai trong vài năm gần đây. Kinh nghiệm của Thụy Sĩ chỉ ra rằng, các công viên đổi mới sáng tạo nên tự coi mình là doanh nghiệp độc lập, có hoạt động kinh doanh khả thi và theo đuổi sự bền vững tài chính. Để đạt được điều này, các nhà quản lý nên được trao quyền tự chủ cao trong hoạt động của mình.

Điều này rất rõ ràng ở Biel, nơi công viên đổi mới sáng tạo được cấu trúc như một công ty có ban giám đốc và tất cả các giám đốc điều hành đều là cổ đông. Ở Zurich và Lausanne, nơi các cổ đông đại chúng vẫn chiếm đa số, cả hai giám đốc đều thể hiện quyền sở hữu của họ trong việc xác định những gì cần làm và huy động nguồn lực ở đâu để làm được điều đó.

Tại tất cả các công viên đổi mới sáng tạo, sự gắn kết với doanh nghiệp là điều sống còn. Việc thành lập SIPBB ở Biel là kết quả của một loạt buổi phỏng vấn với các giám đốc điều hành công ty và chủ doanh nghiệp vừa và nhỏ về những gì họ cần. Không có gì ngạc nhiên khi những doanh nghiệp này trở thành khách hàng của SIPBB. Tại Zurich, giám đốc công viên đổi mới sáng tạo Zurich (IPZ) đang sắp xếp thỏa thuận với một công ty bất động sản lớn để chuyển đổi các nhà chứa máy bay và sân bay thành không gian làm việc chung, không gian sản xuất và văn phòng. Tại Lausanne, Công viên đổi mới sáng tạo EPFL đang bắt tay với các đối tác để phát triển một “quận” đổi mới sáng tạo – bao gồm cả các khu nhà ở, thương mại và dịch vụ.

Như hầu hết các công viên khoa học công nghệ ở Việt Nam, các công viên đổi mới sáng tạo của Thụy Sĩ cũng nhắm đến các tập đoàn như một nguồn doanh thu bền vững và thịnh vượng. Nhưng làm thế nào mà hệ sinh thái đổi mới sáng tạo có thể thu hút được các tập đoàn tham gia? Không có bí quyết riêng gì ngoài việc nỗ lực và chăm chỉ. Việc thu hút các tập đoàn là thách thức ở khắp mọi nơi, không chỉ riêng Thụy Sĩ hay Việt Nam. Vì vậy, nếu làm việc chăm chỉ vẫn không được thì người ta cần phải làm việc chăm chỉ gấp đôi, các chuyên gia Thụy Sĩ cho biết.

Mike Baur, đồng sáng lập kiêm giám đốc điều hành quỹ đầu tư mạo hiểm Swiss Ventures Group đã cố gắng rất nhiều để tiếp cận các tập đoàn. Ông chia sẻ công thức tại hội thảo Peer Exchange Meetup 2022: “Hãy lập danh sách 10 tập đoàn mới vào thứ Hai. Gọi cho họ vào thứ Ba để sắp xếp các cuộc gặp. Và đừng bao giờ lên lịch các cuộc gặp vào thứ Sáu, về cơ bản đó là cuối tuần tại các tập đoàn!”

Ngoài việc giới thiệu với các giám đốc doanh nghiệp về tiềm năng của startup và những sản phẩm, dịch vụ mà họ tạo ra có thể giúp ích gì cho doanh nghiệp thì các tổ chức hỗ trợ đổi mới sáng tạo có thể thử tiếp cận theo cách ngược lại: Dành thời gian đồng cảm với các doanh nghiệp, từ đó xây dựng một danh sách những vấn đề mà doanh nghiệp đang đối mặt rồi tổ chức những chương trình thúc đẩy các nhà sáng lập và các nhà đổi mới sáng tạo tìm kiếm giải pháp cho những vấn đề đó.

Đại học như một nguồn cung cấp tài năng và tri thức

Rõ ràng là các công viên đổi mới sáng tạo phải được đặt gần các trường đại học như một nguồn liên tục cung cấp nhân lực tài năng và kiến thức mới. Thực tế, cả ba công viên đổi mới sáng tạo ở Biel, Zurich và Lausanne đều có cổ đông là các trường đại học.

Mặc dù có rất nhiều trung tâm đổi mới sáng tạo và khởi nghiệp ở Việt Nam cũng nằm trong các trường đại học, nhưng điều cần làm nổi bật là chất lượng nguồn nhân lực. Điều này không có nghĩa là nguồn nhân lực ở Việt Nam không tốt. Tuy nhiên, so với Thụy Sĩ, các trường đại học như Đại học Khoa học Ứng dụng Bern, Viện Công nghệ Liên Bang Thụy sĩ ETH Zurich hay Viện Kỹ thuật Liên bang Lausanne EPFL đang đứng trong top đầu thế giới về nhiều ngành kỹ thuật ứng dụng và nghiên cứu cơ bản.

Để tạo động lực cho đổi mới sáng tạo, các trường đại học trọng điểm ở Việt Nam phải đầu tư thêm rất nhiều vào đội ngũ nhân lực (giảng viên, sinh viên, nghiên cứu sinh…) của mình theo hướng đổi mới sáng tạo. Đại học đổi mới sáng tạo là một mô hình mới. Nếu mô hình đại học nghiên cứu hiện nay chú trọng vào hai nhiệm vụ chính là đào tạo và nghiên cứu khoa học thì giờ đây các trường theo định hướng đổi mới sáng tạo sẽ có thêm vai trò mới là nơi tạo ra các “giá trị” cho sự phát triển của doanh nghiệp và cộng đồng./.

LikeLike